No, it wasn’t just you. The Yankees and Rays began the season by shifting more than any two teams in baseball.

Entering Thursday, Tampa Bay had shifted 44 times in its three games against New York—the second-most in baseball—and the Yankees ranked sixth with 26. That’s 70 freaking infield shifts. To provide some context, the Cubs—a great defensive club—shifted just four times over their first three games and the Red Sox shifted three times. So, it’s not like the entire league was shifting over 30 times, this was an exceptionally high amount of shifts for a three game series to see.

And, for the most part, they were pointless. The Rays surrendered 12 hits against their 44 shifts (a .273 batting average) while they picked up nine hits against New York’s 26 (.346).

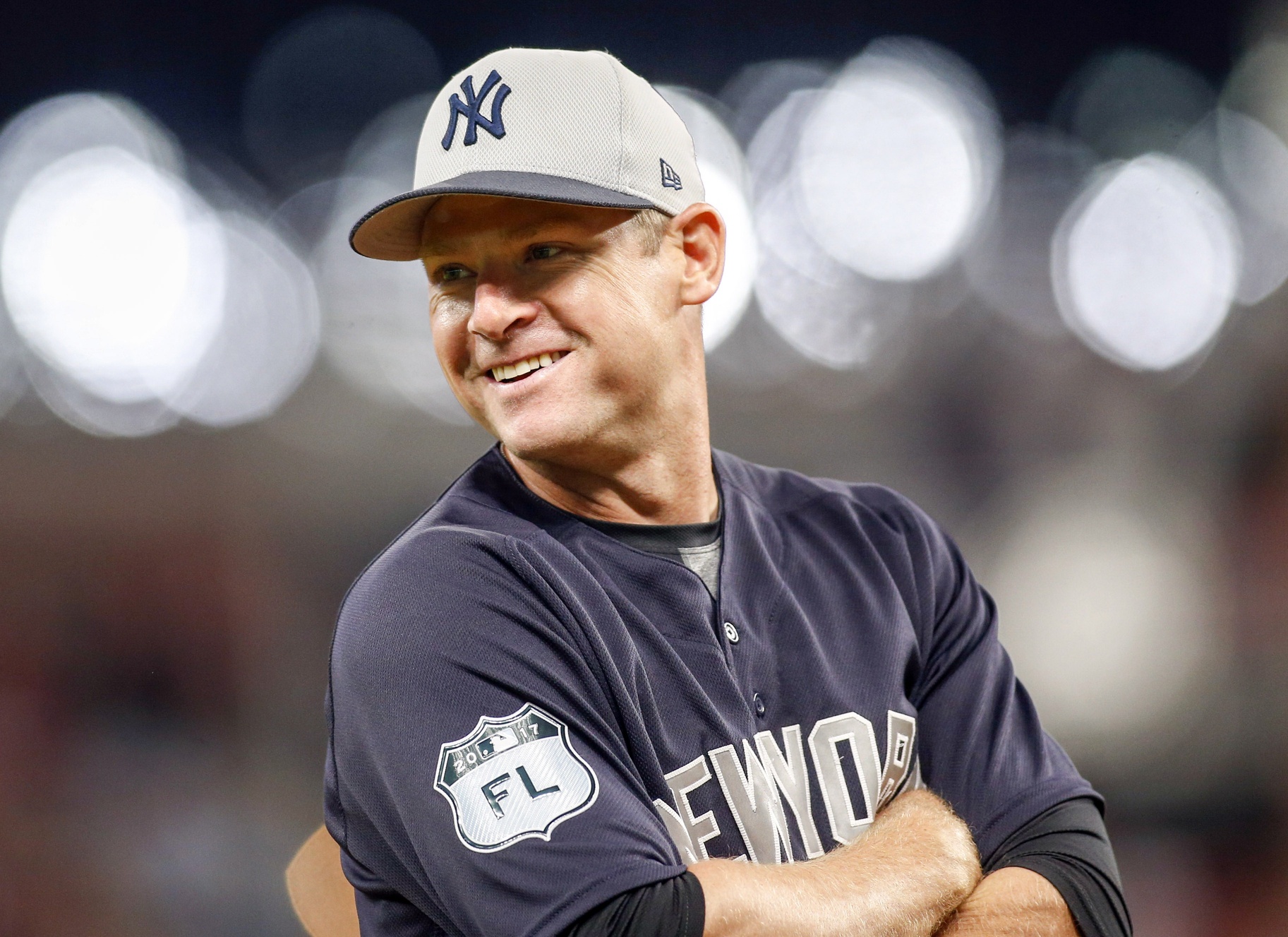

The biggest beneficiary of this trend was Chase Headley—a career spray hitter—who decided to just go the other way on a few occasions when Tampa Bay shifted him:

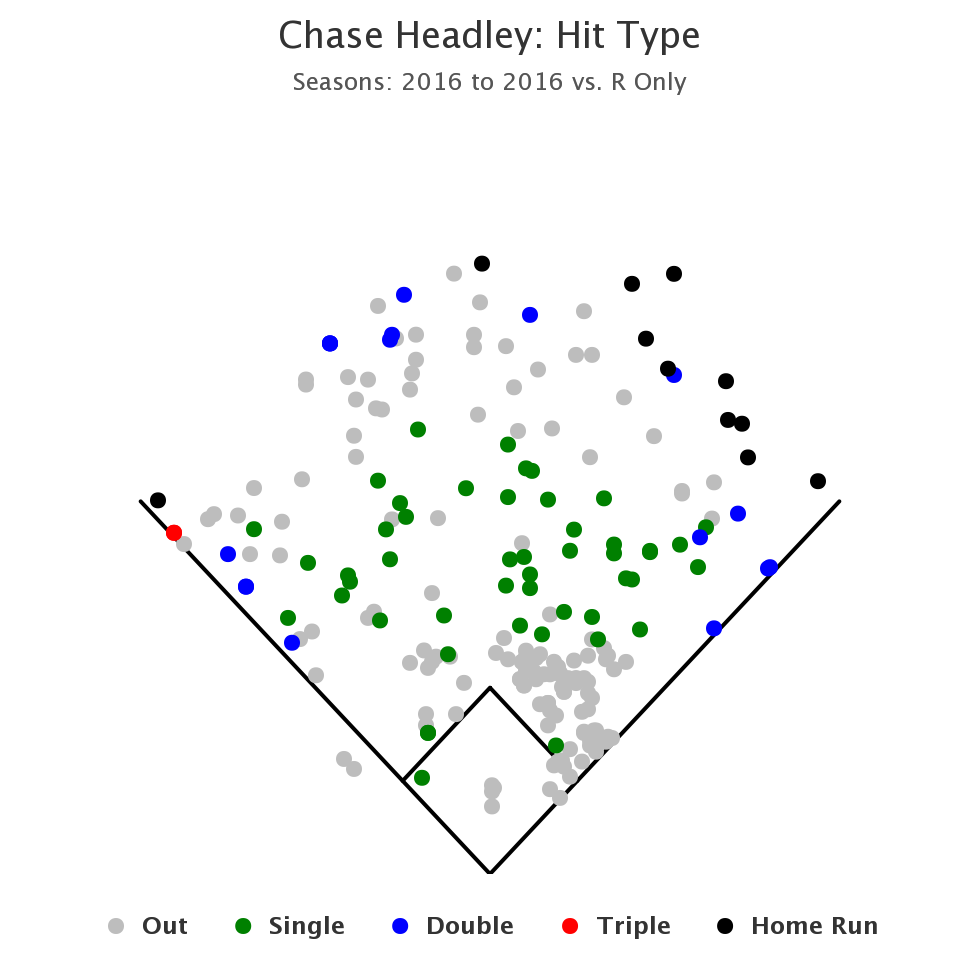

Headley’s case seemed to the public to be a perfect example of why not to shift a player based on recent trends. The switch-hitting third baseman actually pulled under 42% of his batted balls last season, his lowest mark since 2011. He certainly favored the right side as a left-handed hitter, particularly as the season came to an end, but displayed the ability to go the other way on countless occasions:

Put bluntly: The Rays and Yankees overmanaged the living daylights out of their opening series, and shifted more times than they needed to. Headley was the most drastic example of a player benefitting against the shift, but as the Rays’ .346 average against the shift showed, there were plenty of hits to go around.

Now, to be fair to both teams, it’s not like every one of the hits they allowed against the alignment was a total failure. Their totals count every single shift, so technically this stumble by Tampa Bay’s Brad Miller qualifies. The shift actually put him in position to make this play.

And, there’s nothing the Yankees were going to do to stop this line drive up the middle:

That said, however, the latter shift was completely unnecessary, because a line drive up the middle is going to be a hit nine times out of 10. There’s been a rise in the number of shifts each of the past five seasons, so we’re going to start seeing a lot more of these unnecessary adjustments. The key to defensive shifting is to pick your spots; you ultimately want to prevent more hits than you surrender, and by shifting over 40 times over a three-game series you’re putting that goal further out of reach.

This is a small sample, and the overall success of these two clubs when shifting will ultimately take shape over the course of the entire season. But if this is a sign of things to come, we’re going to see an enormous amount of defensive shifts from these two in 2017.

Photo: Brett Davis/USATSI