I often wonder if Alex Rodriguez still thinks about the ninth inning of Game 4 in the 2004 American League Championship Series. The Yankees had a 4-3 lead when that inning began, a lead A-Rod helped build when his two-run home run broke a scoreless tie six innings earlier. The team was on the precipice of a second-straight pennant and an emphatic sweep of the rival Red Sox. It was only his first season in New York, and Alex was just three outs away from realizing his dream of playing in the World Series.

In some parallel universe, I imagine, it comes true for him. There is no Kevin Millar walk, no Dave Roberts steal. A-Rod doesn’t have to watch helplessly as Bill Mueller slaps a single up the middle to tie the game, sparking one of the most improbable sequences in the history of sports. In that world, Mariano Rivera gets his three outs. A-Rod wins the series MVP with a .368 average and a pair of homers, then goes on to help the Yankees defeat St. Louis a week later. A-Rod is the prince who was promised, the sport’s most electrifying talent merged with its most famous team, and he succeeds in restoring them to glory on his very first try.

That reality slowly melted away of course, beginning in that ninth inning. The walk, the steal, the single, David Ortiz’s home run three innings later…each pulled A-Rod further and further from that universe. When the dust settled a few days later and the collapse was complete, there was no longer any notion that A-Rod could be a hero in New York. The prophecy had been rewritten.

There’s no way that he or anyone else could have possibly known what would unfold in the hours, days and even years to come when that half-inning began. In retrospect though, that inning, one in which he was no more than a bystander, may have been the most pivotal of his career.

***

The 2004 collapse was unlike anything Yankee fans had ever experienced. No baseball fan anywhere had experienced anything quite like that really, but that brand of pain was particularly foreign to fans of a team that had dominated the sport for a century and was fresh off a dynasty that yielded four championships. There were losses, of course. The loss to Arizona in 2001 was heartbreaking, and the one to Florida in 2003 incredibly frustrating. Those were baseball losses though, wounds that would heal with time. The loss to Boston was a different kind of animal. It was personal, and it would not heal, maybe not ever.

All of the elements that made the series so euphoric for Boston — the heat of the rivalry, the 3-0 comeback, overcoming the ‘curse’ — are precisely the elements that made it so agonizing and rage-inducing for New York, and Yankee fans needed someplace to direct that rage. They could not in good conscience turn on their own, the men that had already helped hoist trophies. It didn’t matter that Rivera blew two save opportunities or that Derek Jeter hit .200 with a .567 OPS in the series. It didn’t matter that Joe Torre was the man at the helm, presiding over the biggest collapse in baseball history. Those guys were Yankees.

Alex wasn’t. He was an outsider, and one who was unlikeable long before he begged his way out of Texas and showed up in the Bronx nine months prior. As the highest-paid player in history, he was the biggest target, and as someone whose insecurity was frequently perceived as insincerity, the easiest. Other mercenaries that were much more responsible for the loss to Boston were largely let off the hook. Kevin Brown and Javier Vazquez, architects of the Game 7 bludgeoning, weren’t long for New York, and Gary Sheffield, 1 for 17 over the final four games of the series, was mostly left alone.

That left Alex to bear responsibility for the most catastrophic loss in franchise history, as well as each additional playoff failure in the years that followed. He was branded a choker in his MVP 2005 season after a lackluster divisional series against the Angels (one where he still managed a .435 OBP). A year later, Torre embarrassingly dropped him to eighth in the lineup in the deciding game against Detroit. He posted one of the great seasons in team history in 2007 en route to another MVP award, but another early playoff exit nullified the accomplishment.

Each fruitless October was a reminder of the collapse, another turn of the 2004 dagger in every fan’s stomach. A-Rod came to symbolize that failure for many, and he was treated as such. A clutch base hit or walk-off home run bought him only enough goodwill to last until his next at-bat.

By the time A-Rod erupted in the 2009 playoffs and helped carry the team to their 27th title, the ship had sailed on his ability to truly win the crowd over. Fans cheered him when he hit game-saving home runs that October, and he was afforded perhaps a slightly longer leash for a time, but he would never be loved the way he wanted to be, the way that Jeter and the rest were. Two years later, the Yankees were back to getting bounced out of the ALDS and the tides once again began to turn. In 2012 he was getting pinch-hit for late in playoff games and some doubted that he’d ever play for the team again.

***

Aside from his often otherworldly production, A-Rod didn’t do much to help his cause. He remained largely unlikeable, first with a demeanor that came across as phony and dishonest, and later when his PED-use came to light. These were mistakes to be sure; there’s no question that he is owed a great deal of the blame for how he has been received over the years. Still, A-Rod never seemed to be afforded the same benefits as others who committed similar crimes. Players like Barry Bonds and Manny Ramirez grew to be reviled by many for committing the same performance-enhancing sins, but always seemed to draw the home-crowd adoration that so alluded A-Rod.

As time went on, it became clear that the disdain for him went beyond just the crowd and permeated the Yankee organization itself. From the ‘A-Fraud’ revelation in Torre’s book, to Brian Cashman explicitly telling him to shut up in the press, to repeated reports that ownership was attempting to find loopholes in his contract — whether by snatching away his home run bonuses or voiding the deal entirely — evidence of his unwelcomeness piled higher over the years.

Through it all, A-Rod continually professed his love for the Yankees through both words and actions. He was on his way to becoming the greatest shortstop in history when he abandoned the position in deference to an inferior Jeter, opting to learn third base if it meant donning pinstripes. After the ill-received decision to opt-out of his contract following the 2007 season, he essentially jettisoned his agent in effort to return to the team. Even now, after years of being underappreciated, he accepted the Yankees’ offer of what is essentially a forced retirement in order to remain in the organization in an advisory role.

Yet even on his way out, the Yankees can’t seem to stop snubbing him. After the retirement announcement was made earlier this week, Joe Girardi claimed that he’d get A-Rod into every game, culminating in a final send-off at Yankee Stadium on Friday before the team unconditionally released him. Girardi then reneged on his promise, saying, “My job description does not entail farewell tours.” It’s hard not to read that as an insult, as Girardi oversaw perhaps the most famous farewell tour of all just two years ago when he let the 40-year-old Jeter hit .256/.304/.313 for 634 plate appearances that came almost exclusively from the second spot in the lineup, and play 130 games of statuesque defense at shortstop for a contending team.

It’s not hard to read between the lines. Whether they remained productive or not, players like Jeter and Rivera were deemed worthy of yearlong fanfare in their final seasons. Similarly, Andy Pettitte rode off into the sunset in much the same way that Ortiz will later this year, celebrated and beloved despite his past transgressions. There will be no fanfare when A-Rod retires. There will be no stadium tour, no gifts, no ovations from crowds across the country. He will likely never see his number retired or his face on a plaque in Monument Park. His climb toward Cooperstown will be steep, maybe impossibly so.

***

The tragedy of Alex Rodriguez isn’t that he cheated, and it isn’t that he lied. The tragedy is that after 22 years in the big leagues, he remains a player without a home; that no matter how much love he gave to this game and this team, he never got it in return. One of the greatest baseball careers that any of us have ever seen will soon be over, and it will go out with a whimper, on a rainy Friday night in August. It’s a shame we didn’t appreciate it more.

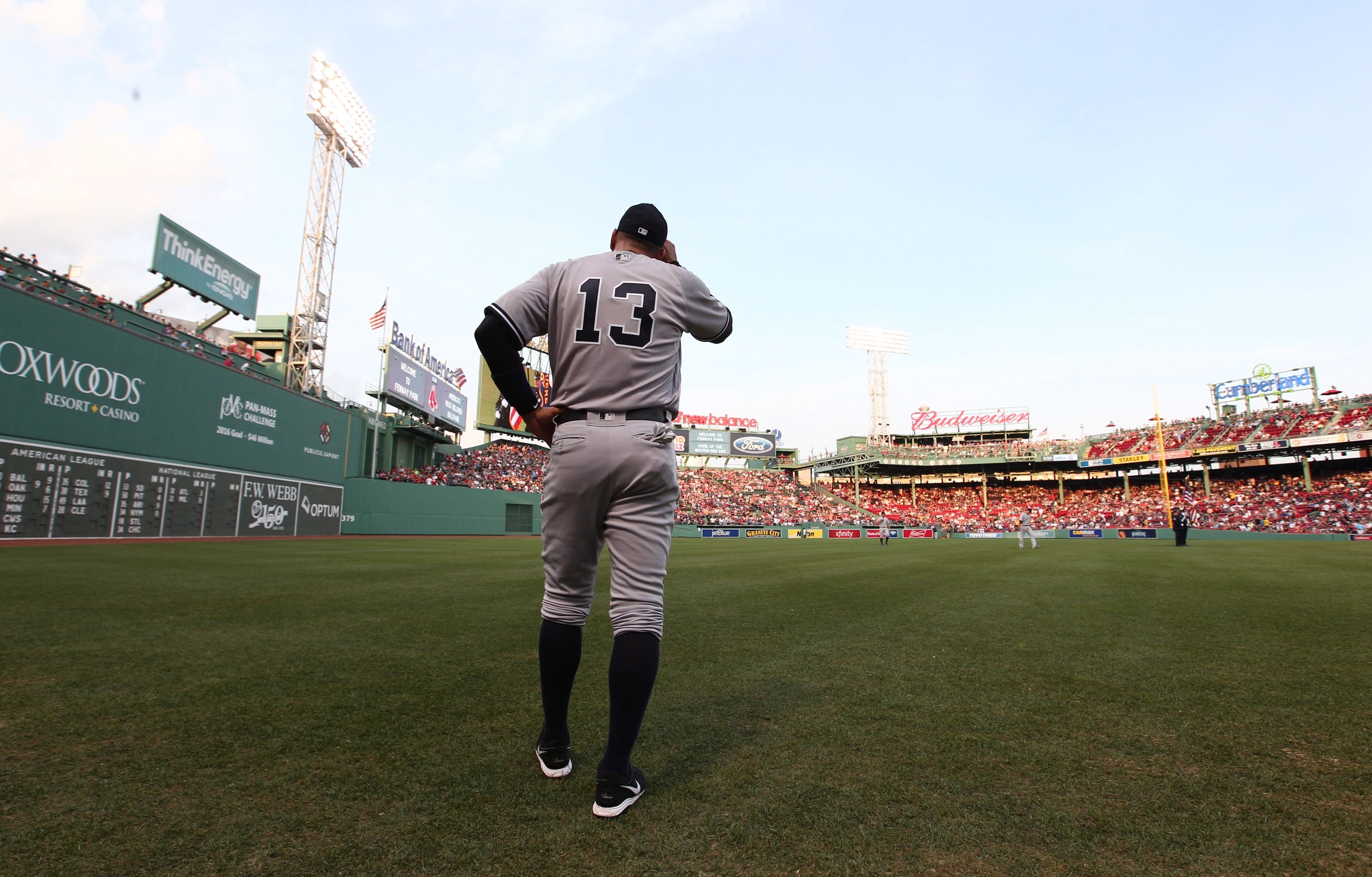

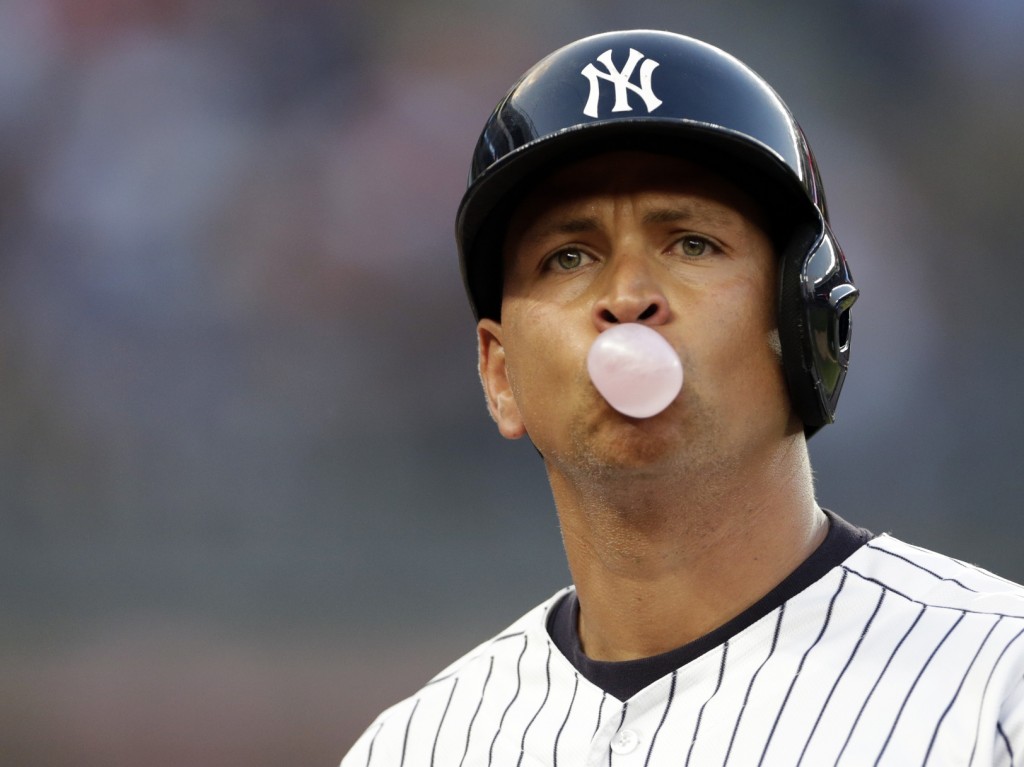

Lead photo: Mark L. Baer; Andy Marlin; Adam Hunger / USA Today Sports

Decidedly missing from your account of A-Rod’s career was his all-out attack on everyone regarding the Biogenesis scandal, including the MLBPA, his own team, and the team’s doctors, before admitting the truth.

The best of A-Rod as a human being came after he had disgraced himself in that scandal. He finally accepted his limitations, and that humanized him in a way we hadn’t seen before.

His story is sad, perhaps, but not tragic. To paraphrase Bill James in another man’s tale, A-Rod was too well paid for tragedy.

I wasn’t in the clubhouse, but when Girardi says, “He didn’t do the work,” in response to why AR was denied a starting slot at 3b, it suggests to me a pretty good all-around judgement on this guy. Blessed with unparalleled talent, he chose to cheat and take shortcuts all along the way. It says quite a lot about a guy when he is so incredibly gifted, yet none of his teammates stand up for him. Too bad AR wasn’t blessed with the character and integrity to match his immense talent. For most of us, AR represents the worst of the sport, and I suspect he will always be remembered so.

What created A-Rod? $ did I wish I were old enough to “compare” A-Rod to a Mays, an Aaron, a Mantle, etc. etc. etc.

A different time, a different “winning” mentality, not on the players part, but on the team owners part. Was it to win or to make them money. The fans buy the tickets, by the jerseys, buy the $8 beers. The “cost” of hopefully winning created A-Rod.